Assistant Professor Brian Theyel, M.D., Ph.D., and his lab partner, Frederic Pouille, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neuroscience, have received a Zimmerman Innovation Award in Brain Science from the Carney Institute for Brain Science. The pair will use the $132,000 award to test how different uses of low-intensity focused ultrasound affect the flow of information from the brain's sensory cortex to the thalamus. Theyel and Pouille hope their discoveries will help clinical researchers develop interventions for sensory processing disorders, such as schizophrenia or autism.

“This collaboration between basic neuroscience and psychiatry at Brown is in its relative infancy but growing,” says Theyel, who began working with Pouille a year-and-a-half ago. “An award like this is directly in service of the interface between these two very successful departments. It’s extremely exciting to be a part of.”

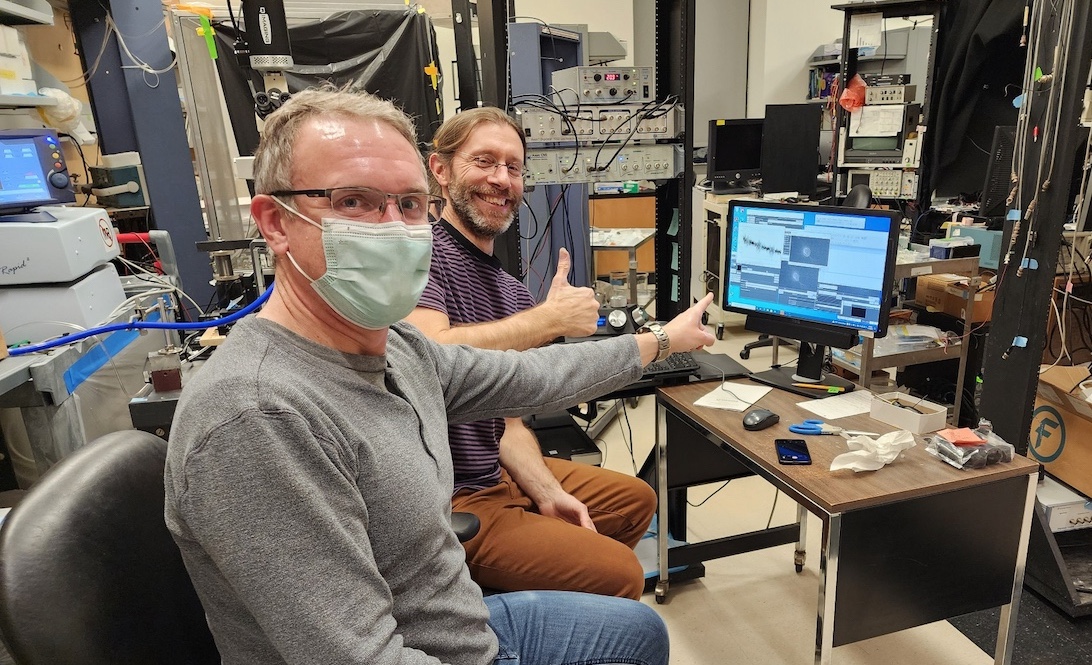

Their lab, located in the Life Sciences Building at Brown, represents a unique collaboration – in part because so few researchers have Theyel’s crossover training in both neuroscience and psychiatry. He is one of the only, if not the only, faculty in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior conducting basic neuroscience research in the Department of Neuroscience. His collaboration with Pouille positions their lab at the intersection of foundational brain research and clinical applications.

“One really valuable thing about working with a neuroscientist is remembering to be humble,” Theyel says. “Psychiatry is a field with a long history of accidental discoveries. Many of our hypotheses have turned out to be wrong or not nearly explanatory enough for many patients, because understanding treatment effects is complicated. We’re going to need to get down to the level of individual circuits in the brain to understand which symptoms of disorders are modifiable and how.”

Pouille and Theyel will focus on two important neuron pathways connecting the neocortex to the thalamus. One pathway mediates the flow of sensory data, while the other shapes it. The researchers plan to use different deliveries of ultrasound – in length, frequency, and strength, for example – to try to selectively activate one pathway or the other while targeting the same area. Professor Linda Carpenter, M.D., a collaborating investigator on the project, will provide technical assistance with the focused ultrasound stimulation system.

While the study will be conducted on brain tissues of mice, Pouille and Theyel anticipate that clinical researchers will be able to use their data as a blueprint for developing focused ultrasound treatments in humans. Focused ultrasound is an attractive treatment option for mental health disorders because it can reach deep brain structures noninvasively. Doctors could potentially use this research to tweak different circuits in individual areas, thereby opening the door to using focused ultrasound for new disorders.

“Coming from basic science, I’m really focused on the minutiae of what is happening in the brain,” Pouille says, “but thinking from a clinical point of view is powerful and, I think, necessary. Doctors need a bank of information about how the brain works.”

In the near-term, Theyel and Pouille will begin by fine-tuning their equipment and ultrasound delivery protocols. They expect to start data collection in approximately five months.