On the eve of his trip to Ukraine, Noah Philip, M.D., packed nervously.

The bulletproof hoodie he’d bought online would be as useful as his Oxford shirts in the event of a Russian missile strike. And the tools of his trade – a textbook, training packets, and tape measures – made for a meager kit compared to the enormity of his mission.

Philip, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior and a psychiatrist at the VA Providence Healthcare System, had been invited to Ukraine to share his expertise in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a non-invasive treatment for PTSD that uses magnets to alter brain activity. His specific charge was to teach providers at a hospital in Lviv how to use their TMS machine – an old, donated Italian model of hazy provenance that was so prone to overheating, hospital staff were afraid to use it. Ahead of his trip, they sent Philip the only manual they had. As far as he could tell, it didn’t match their machine.

Yet he couldn’t let them down. After two years of invasion, the need for trauma relief in Ukraine is extensive – veterans returning from the front lines, torture survivors, and civilians living under constant threat of attack.

“I’m nervous about the risks,” Philip said the day before his mid-November flight. “But I’m also nervous I’ll get there and not be able to help the way I want to.”

What he could not have imagined was the way the Ukrainian approach to trauma – improvisational by necessity – would reshape his own assumptions about the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Welcome to Ukraine

Philip’s route to Ukraine began with a talk he gave at Yale last year. A psychologist in the audience, Ilan Harpaz-Rotam, Ph.D, ABPP, reached out afterwards with a proposition: Would Philip consider joining him on a trip to Ukraine? He thought Philip’s TMS expertise could be helpful to a trauma recovery center he’d helped establish there.

Philip’s initial reaction was simple: No. He had a young family, after all. But the idea lingered.

“A core Jewish value in my heart is the spirit of tikkum olam, or ‘repairing the world,’” Philip said. “The singular goal of my career is to make this world a better place. Here was an opportunity to do exactly that, but on a scale I never thought would be available to me."

With his family’s blessing, he decided to go. On Nov. 8, Philip flew to Krakow, Poland where a driver picked him up along with Harpaz-Rotam. (Ukrainian airspace is closed to commercial flights.) After a five-hour wait at the Ukrainian border, they crossed into a different world: A darkened countryside with uprooted road signs meant to foil would-be attackers.

Their destination, Lviv, is a city about two hours from the border, far west of the front lines. Yet come daylight, Philip could see signs of war everywhere: Boarded windows. Craters. Generators at the ready. Public statues mummy-wrapped in fireproof shrouds. Office workers in practical clothes, ready to run at an air raid siren’s blast.

For his part, Philip downloaded an app to alert him of falling missiles and took note of the shelter in his hotel basement. Before his five-day stay was through, an alert would send him scurrying there.

A People Unbroken

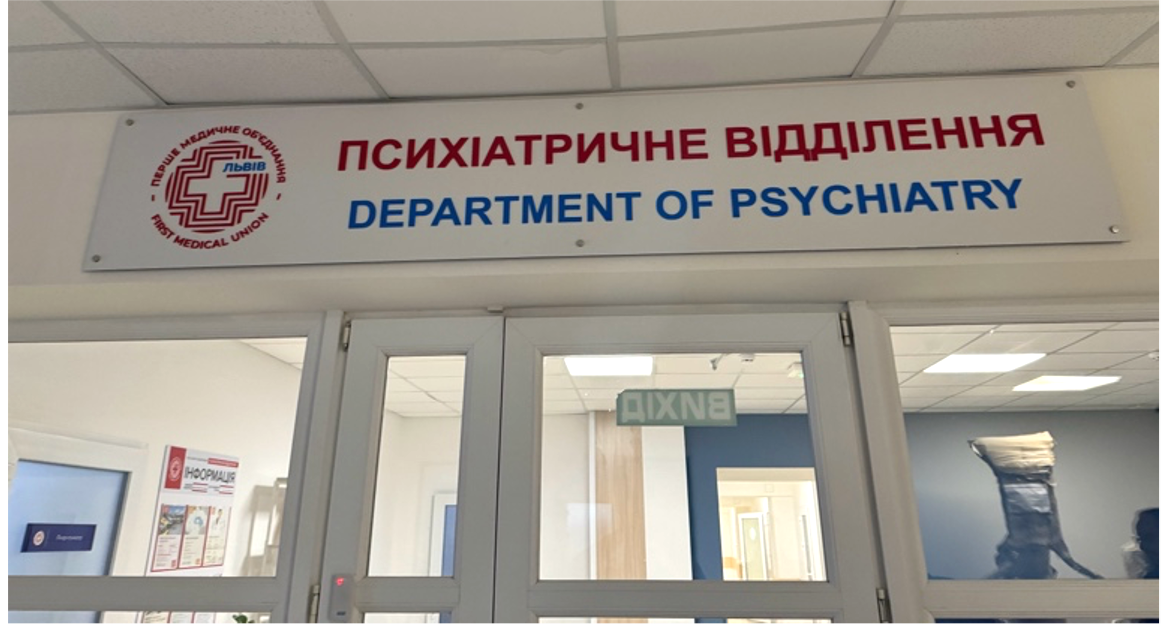

Philip, Harpaz-Rotam, and his colleague Shelley Amen, M.D., Ph.D., came to Lviv at the behest of Unbroken, a nonprofit founded by two military volunteers who had lost limbs in the war. Their goal is to provide physical and psychosocial rehabilitation to Ukrainians affected by war. Practically speaking, this meant the medical center Philip visited paired two disparate units: Psychiatry and surgery.

In the surgery ward, Philip found patients sleeping six-to-a-room and with limited access to medicine. All opiates are needed at the front lines, he learned. Even blood pressure medications go unused, because one nurse can’t check vitals often enough for the 20 patients under their care. And instead of sleeping pills, the hospital relies on eye movement desensitization – a technique for easing traumatic memories – to help its patients sleep.

“I’m a skeptic, but I kept my mouth shut,” said Philip, who was glad he had. By the end of his trip, he was convinced that whatever the evidence base, the method worked remarkably well.

In the psychiatry unit, Philip met patients coping with raw, deep traumas. One patient, a military sergeant, had just lost three limbs in the war and stayed up each night to guard his roommates. Many torture survivors had gone completely mute.

“I saw EEGs that showed a complete absence of normative brain rhythms,” Philip said. “I’ve never seen anything like that.”

At the same time, he’d also never seen anything like the Ukrainians’ creative approaches to treating mental suffering. In addition to art therapy, the hospital provided patients with a uniquely Ukrainian therapy: Weaving. The therapy employs a traditional Ukrainian loom, which requires simultaneous use of hands, feet, and mind to weave a repetitive pattern.

“The weaving was brilliant,” Philip said. “It’s a great example of culturally focused rehabilitation. I’d like to help them disseminate findings on these things they’ve learned to do.”

Man Versus Machine

At Unbroken, Philip gave multiple lectures on TMS with the aid of translated slides and an interpreter who relayed two-way communication through headphones. But the true test of his expertise arrived when he came face-to-face with their machine. At a glance, it didn’t look too formidable: A console on a shelf hooked up to a laptop and a magnetic wand. Through an interpreter, though, he learned hospital staff wouldn’t touch the thing, which spiked in temperature the moment it powered on. Only the doctors had tried using it.

Before he could train their team, though, Philip had to determine what the TMS machine could do. Straightaway, he discovered that their over-hot system actually emitted weak energy. That meant the first step in a TMS treatment – the motor threshold test – would pose an extra challenge. Instead of conducting a simple finger-twitch test to establish a patient’s motor threshold, they would have to use an electromyogram, a complicated electrode-involved workaround that Philip hadn’t used in a decade.

Like a test pilot, Philip also tried pushing the TMS machine to its limits. He found that the machine’s rapid heating eventually plateaued, allowing 30 minutes of high-output operation. Based on his tinkering, he created algorithms the Ukrainians could use to calculate how much energy was needed, for how long, and for which patient motor thresholds.

In a matter of days, Philip trained the medical team how to provide TMS clinical care – instruction that would normally unfold over a month with Brown psychiatry residents. To shore up the Ukrainians’ speed-training, he left them with learning materials, notes, and skills checklists, and designated a point person to contact him as questions arose.

“Initially, only physicians were using their TMS machine,” Philip said. “Now, after a physician establishes a patient’s motor threshold, a technician should be able to deliver TMS. That allows you to increase your scale considerably. Hopefully, they can treat a lot more people.”

A Lasting Connection

Of Philip’s many lines of work, the Ukrainians homed in on one study in particular: Mobile TMS for veterans in rural Montana, which is provided through the VA system. Did this mean, they wondered, that TMS could be brought to the front lines of war, as well?

The question laid bare the grim calculus of an existential war. A non-pharmacological PTSD treatment, such as TMS, would enable traumatized soldiers to return to battle sooner. There is some evidence, Philip noted, that TMS may help prevent retraumatization, as well.

Since leaving Ukraine, Philip has continued to collaborate with his counterparts at Unbroken. He has connected them with a manufacturer of reliable TMS machines, in case a donation is possible, and is raising funds for new devices. He is also helping them pursue avenues of research into their innovative treatments.

“Their ideas could be really helpful for other complex conflict zones,” he said.

Meanwhile, he believes the research conducted at Brown and its affiliated hospitals can make a very real impact for the Ukrainians, as well.

“Here, we see particularly terrible PTSD in veterans who were not professional soldiers – people who were in the private sector one day and in a war zone the next,” Philip said. “That’s the entire Ukrainian military. It’s going to be an enduring challenge they’ll be dealing with for decades. But I think much of what we’ve learned can really help them.”